It will surely go down as one of China’s biggest — and most bizarre — internet hoaxes in years.

For weeks, Chinese social media users were riveted by what seemed like a heartwarming story: An influencer’s attempt to return two lost school books she had found in a Parisian restaurant to their owner.

People across the country joined the search. Posts about the books racked up millions of likes. Theories about the student’s potential identity proliferated. Even a local public security bureau in eastern China got involved.

Then, on April 12, the truth was finally revealed: The influencer, it turned out, had made the whole thing up.

She and her team had fabricated the exercise books, flown them to Paris, and then pretended to discover them in a restaurant toilet. The entire story was a hoax designed to attract traffic that had spiraled way out of control.

The result has been an explosion of public outrage. The influencer’s accounts on several social platforms have been suspended, and public security officials say she will also face legal penalties.

Meanwhile, the incident has once again renewed discussion about the wider issue of influencers making up fake stories to drive engagement — a severe problem in China due to the cutthroat competition among influencer agencies.

Thurman in Paris

The influencer at the center of the controversy is Xu Jiayi, known online by the name Thurman, a 29-year-old who spent a decade in France studying and working in the fashion industry before returning to China in 2022.

After returning home, Xu launched a clothing line and signed with an influencer agency in the southern Guangdong province. With her bubbly personality and sharp comic timing, Xu quickly became a major star on Chinese social media, attracting a combined 40 million followers across her various channels.

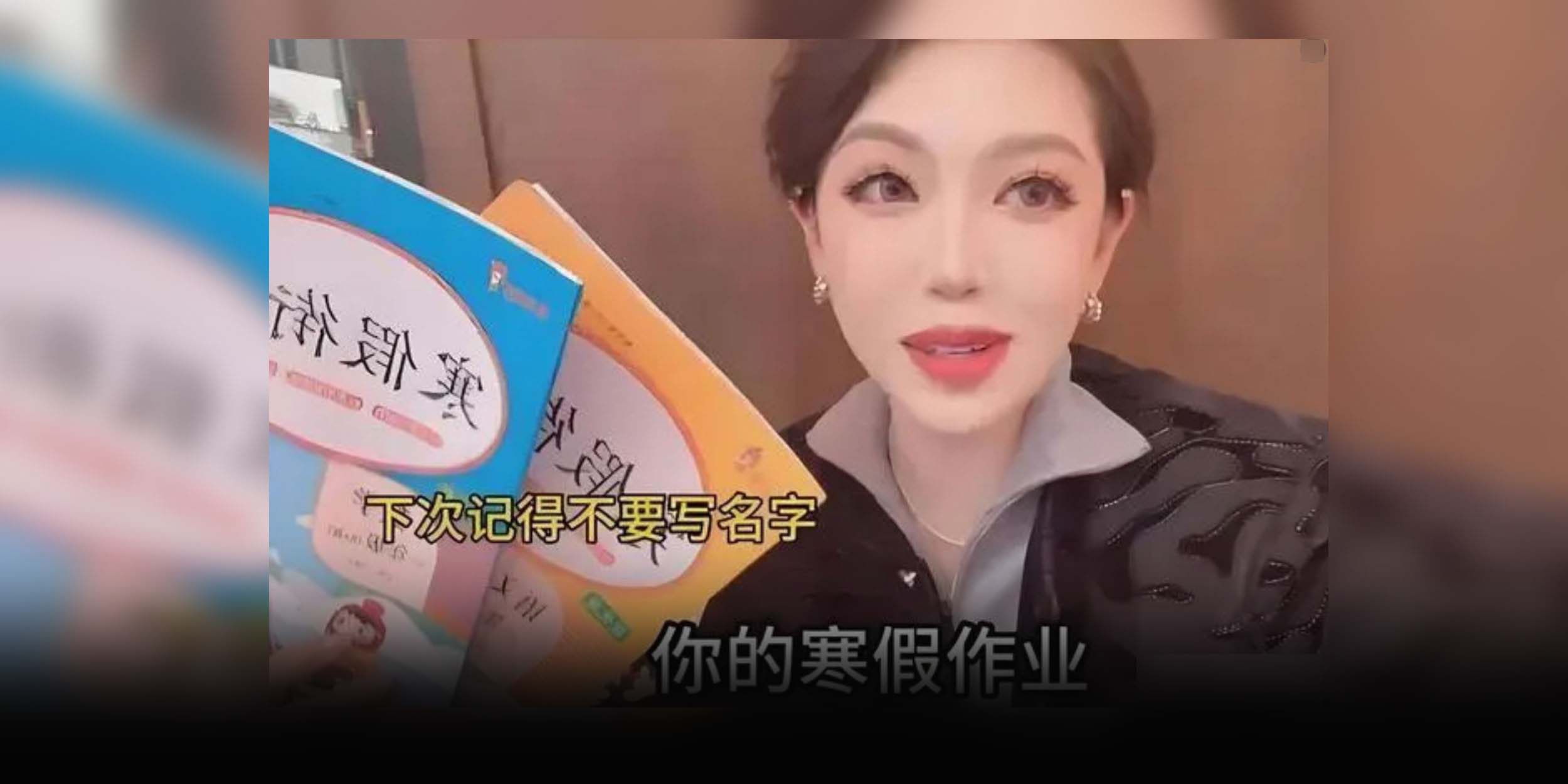

During this year’s Spring Festival holiday, Xu launched what would become her biggest — and possibly final — online stunt. On Feb. 16, she posted a video to her channels about an incident that she said had occurred during a business trip to France.

In the video, a French waiter approaches Xu and hands over two Chinese school books, explaining that he had found them in the restroom. He asks if Xu could help return them to their owner.

Xu then appeals to her followers for help. The books, she explains, appear to belong to a primary school student and are filled with homework exercises.

“Qin Lang from class eight, grade one, your winter vacation homework was left in a toilet in Paris,” Xu says to the camera.

The post went massively viral, receiving over 5 million likes on Douyin, China’s version of TikTok, in just a few days. It also became the third highest trending topic on lifestyle platform Xiaohongshu during the Spring Festival holiday.

“The plot itself is quite appealing. And since it occurred during the Spring Festival and involved traveling abroad, the story hit multiple keywords and quickly became a trending topic,” Zhao Zhichao, captain of the cyber police team at the West Lake District Public Security Bureau in the eastern city of Hangzhou, told Chinese state broadcaster CCTV on Saturday.

Netizens across China began hunting for Qin Lang. One Douyin user posted a comment saying that he was Qin’s uncle, and claimed that the boy attended Xichang Primary School. The post received over 220,000 likes.

When several Chinese media outlets investigated the claims, however, they were unable to find a school named Xichang that had a first-grade student called Qin Lang. The user had his Douyin account suspended for violating community guidelines.

Plot twist

Xu tried to draw a line under the story, posting another video on Feb. 19 in which she claimed that she had found Qin’s mother. But as time went on, doubts about the authenticity of Qin’s identity continued to grow.

West Lake District Public Security Bureau in Hangzhou received so many tip-offs about the story that it decided to have its cyber police unit investigate. After combing through travel records, the team found no records of a student named Qin Lang having flown overseas during the Spring Festival period.

Further investigation revealed the truth: Xu and her colleague at the influencer agency, a 30-year-old surnamed Xue, had planned and executed the hoax together, fabricating the school books, writing scripts for the videos, and then shooting them on their phones. When officers in Hangzhou confronted Xu, the influencer came clean.

“You tell one lie, and then tell many other lies to try and cover your tracks … But in reality, you’re actually just piling more mistakes onto that first mistake,” Xuan Jing, another member of the West Lake District cyber police team, told CCTV. “She admitted that during our conversation — acknowledged that the attention got too intense.”

On April 12, Xu faced the music, publicly apologizing to her fans in a video posted to her social channels. But the confession failed to calm the resulting public anger, with many users particularly upset by the fact that she had continued the hoax for so long.

“You shouldn’t deliberately make up lies and manipulate people’s feelings just for the sake of attention,” read one of the most-liked comments on Xu’s confession on the microblogging platform Weibo.

Public security authorities in Hangzhou announced on April 12 that Xu and her influencer agency would face administrative penalties for “disturbing public order,” though the details of the sanctions are unclear. Xu’s accounts on Douyin, Weibo, and WeChat Video have all been suspended.

Chinese authorities appear to be increasingly concerned about the spread of rumors and false information online. The Ministry of Public Security launched a national campaign on the issue in December, which it says has led to the arrest of over 1,500 suspects.

Many of those cases will be unrelated to the kind of hoax perpetrated by Xu, but influencers spreading fake stories to generate traffic does also appear to be on the rise.

On April 12, the Ministry of Public Security included Xu’s case in a list of 10 high-profile examples of misinformation. Others involved false reports about a mother-in-law being mistreated, disaster relief supplies being resold, and a bank going bust.

Additional reporting: Li Dongxu.

(Header image: A screenshot shows Xu Jiayi holding the homework books in the trending video. From Weibo)